Legacy INDUCTEE

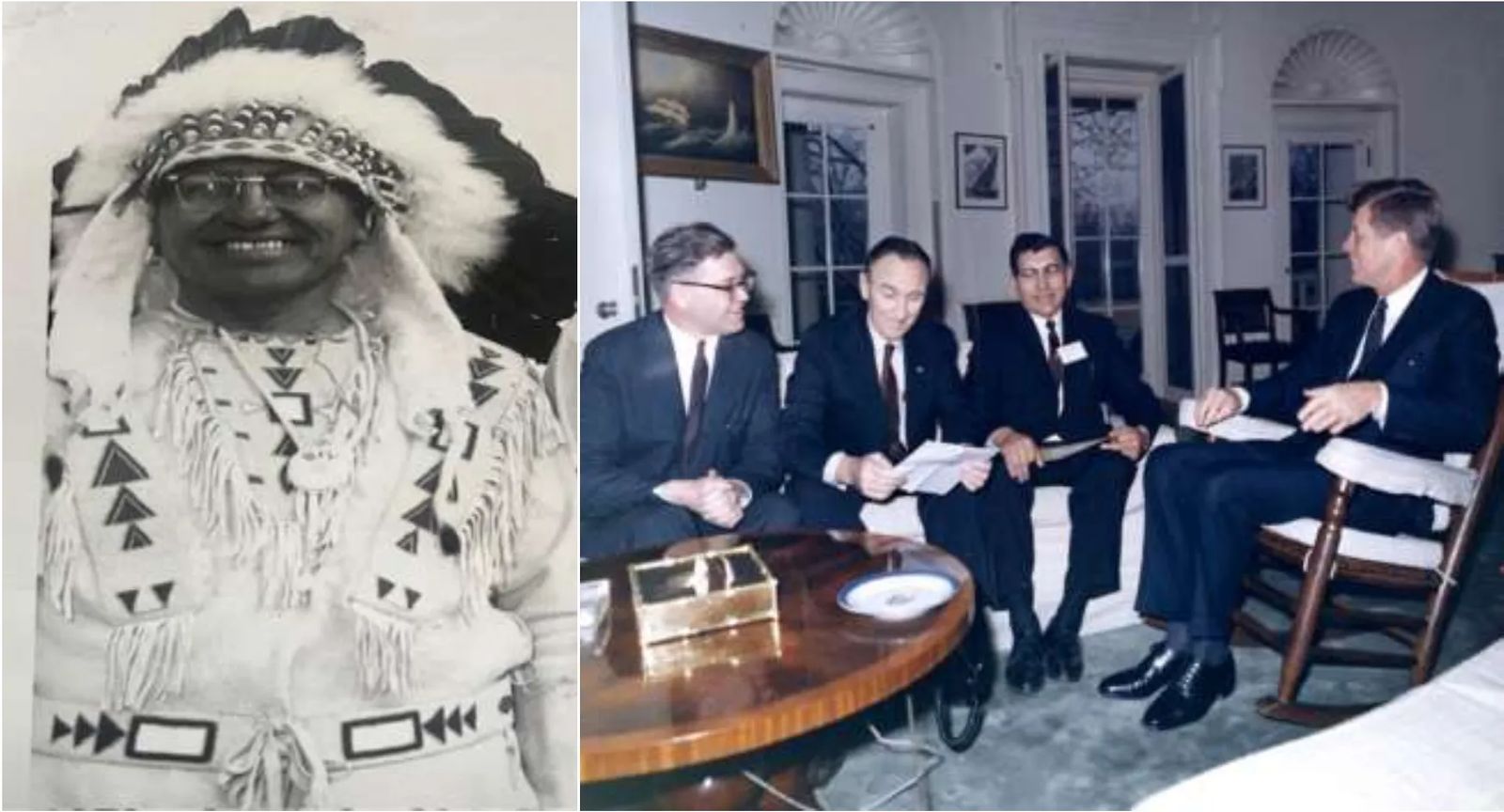

WALTER “BLACKIE” WETZEL

(SIKS-A-NUM) (1915-2003)

DISTRICT 5 - YEAR 2026

Walter “Blackie” Wetzel was born to William and Henrietta (Veileaux) Wetzel on June 27, 1915, near Cut Bank Creek on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation. Walter, whose grandparents included a Missouri River steamboat captain, a full-blooded Blackfeet woman, and a Fort Benton trading post pioneer, became well-known by the nickname “Blackie,” derived from his Indian name (Siks-A-Num) which means “Blackfeet Man” or “Man of the Blackfeet People.”

As a youth, Blackie experienced hardship and adventure. Following his mother’s passing in 1922, and during a trying period in his life, young Walter was sent to the Haskell Institute, a residential boarding school for Native American children in Lawrence, Kansas. Homesickness prompted him, at the age of eleven, and two other Native American students to attempt to catch trains back to Montana in the middle of winter. After several tries, they made it back to their Big Sky Country.

Blackie worked on the family cattle ranch on the Blackfeet Reservation while attending school in Browning, where he claimed to have made the first touchdown in the school’s football program history. He was recruited to play basketball his senior year at Shelby High School by Coach Max Worthington; he graduated after leading their basketball team to the district championship in 1934. Blackie went on to attend the University of Montana, where he was a standout athlete for the Grizzlies; he played football and lettered in track and boxing. Blackie also participated in the ROTC program and studied history and political science under then-professor Mike Mansfield, who later served as a United States congressman and a Montana state senator. Mansfield became Blackie’s mentor and one of his closest friends. They were given the Distinguished Alumnus Award together at the University of Montana in 1990.

While attending Haskell, Blackie learned how to box; he went rounds with a tri-state champion and won the bout, giving him a notion to try his hand on the professional circuit, but his father changed the young brawlers mind and convinced him to stay in school. Blackie's boxing career reached an intramural apex when a 6 feet 3 inches tall, handsome and muscular student named George Letz, from Conrad challenged him. Blackie gave up about six inches in height and more than that in reach; it was a knock-down, drag-out battle, but Blackie managed to pull it off. He recalled hitting his opponent with a twisting jab that split his lip. The defeated pugilist later changed his name to George Montgomery, and went on to become a Hollywood celebrity and star. They remained great friends for years, and Blackie would enjoy pointing out to his sons the still-visible scar on the actor's lip.

At the beginning of World War II, Blackie was studying aeronautical drafting in Helena. Blackie passed a series of tests for men with pilot potential, but an unfortunate health issue kept him grounded. He worked for the United States Air Force as a property and supply clerk for the 840th Special Air Depot at Mather Air Force Base in Sacramento, California.

Upon Blackie’s return to the Blackfeet Nation, he developed a strong interest in tribal politics. Chief John Two Guns White Calf, the last Blackfeet War Chief, conferred upon Blackie his Indian name as well as a chieftainship rite of passage.

Blackie entered politics in 1948; he was elected to the Blackfeet Business Council and became Tribal Chairman in 1950, a position he would hold until 1964. In 1960, Blackie became the first tribal leader from Montana to sit as President of the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), the country’s oldest Native American and Alaskan Native advocacy organization, and served in that role until 1965.

Montana Senators Mike Mansfield and Lee Metcalf, and U.S. Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall were very involved with the NCAI during Blackie’s chairmanship. He met and worked with many great leaders; photos and telegrams can attest that President John Fitgerald Kennedy, whom Blackie named “High Eagle,” became his personal friend.

Blackie also worked for the U.S. Department of Labor and Job Corps to address housing and employment issues in Indian Country. He supported tribal governance and self-determination and traveled to Indigenous communities nation-wide, promoting programs to alleviate unemployment, wealth disparity, and over-crowding. He was known for denouncing asassimilation policies and for his advocacy on behalf of landless Indian tribes. In 1964, in the wake of one of Montana’s biggest natural disasters, Chairman Wetzel and his fellow council members secured relief funding by bringing Secretary Udall to the Reservation to survey historic flood damage near Glacier National Park and experience the resiliency of the Blackfeet people.

In 1971, Blackie drew upon the relationships he built through his career in Washington, D.C. to convince the National Football League’s Washington Redskins team to replace the letter “R” on their helmets with a composite Native American image he designed to honor the country’s first peoples and symbolize their strength, pride, courage, and service. The logo was used for nearly fifty years; Blackie and his Washington Redskins cap were insperable.

Other special interests and events which highlighted his life were dancing with movie actress Donna Reed, drumming for a jazz band, attending mass with the Kennedy family, and riding horseback down Pennsylvania Avenue for the JFK inauguration. He also played the role of a medicine man in the movie Grey Eagle, which was filmed in the Helena area, and was also featured and interviewed by NBC in 1958 for their documentary The American Stranger which focused on legal, economic, and social conditions of Native American populations.

Blackie raised the profile of the Blackfeet people into a national consciousness. He was not only a scholar, an athlete and national-level leader but a family patriarch. In 1938, Blackie married Doris L. Barlow; they shared fifty years of marriage and raised nine children together (Marlene, Bill, Helen, Walt, Don, Mike, Sharon, Christine and Lance). Many of his life's accomplishments were made possible by the love and partnership of Doris, who supported him and their entire family throughout every step of the journey. Blackie’s relatives appreciated his sense of humor, and valued his daily practice of praying for all of his family and friends. Various Wetzel descendents have continued Blackie’s tradition of pursuing education, excellence in athletics, and advocating for tribal causes. Blackie’s beloved wife Doris, passed away in 1988, and Blackie Wetzel, a warrior revered for his kindness, passion and determination, died at the age of 88 on November 8, 2003, in Helena, Montana.

Reference and Source Directive

Walter Wetzel Obituary. Billings Gazette. November 11, 2003. https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/billingsgazette/name/walter-wetzel-obituary?id=6858641

Wetzel, Jr., Don. “Blackie Wetzel’s accomplishments extend beyond logo design.” Great Falls Tribune. July 17, 2020

Maibe, Nora “Who was Walter ‘Blackie’ Wetzel, the Blackfeet Man behind the Washington football team’s logo?” Great Falls Tribune. July 23, 2020

Rachac, Greg. MontanaSport.com. September 29, 2024.

NCAI Current and Past leadership; https://www.ncai.org/about-ncai/ncai-leadership

Interview: Lance Wetzel interview by phone July 14, July 19, 2025

“The American Stranger,” NBC Documentary. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XYvBlWP2HAQ

“Progressive Men of the State of Montana.” A.W. Bowen and Company. Nelce Vielleaux- page 1850. William Scott Wetzel, page 1862. https://archive.org/details/progressivemenof01bowe/page/n1161/mode/2up