MONTANA COWBOY HALL OF FAME LEGACY INDUCTION

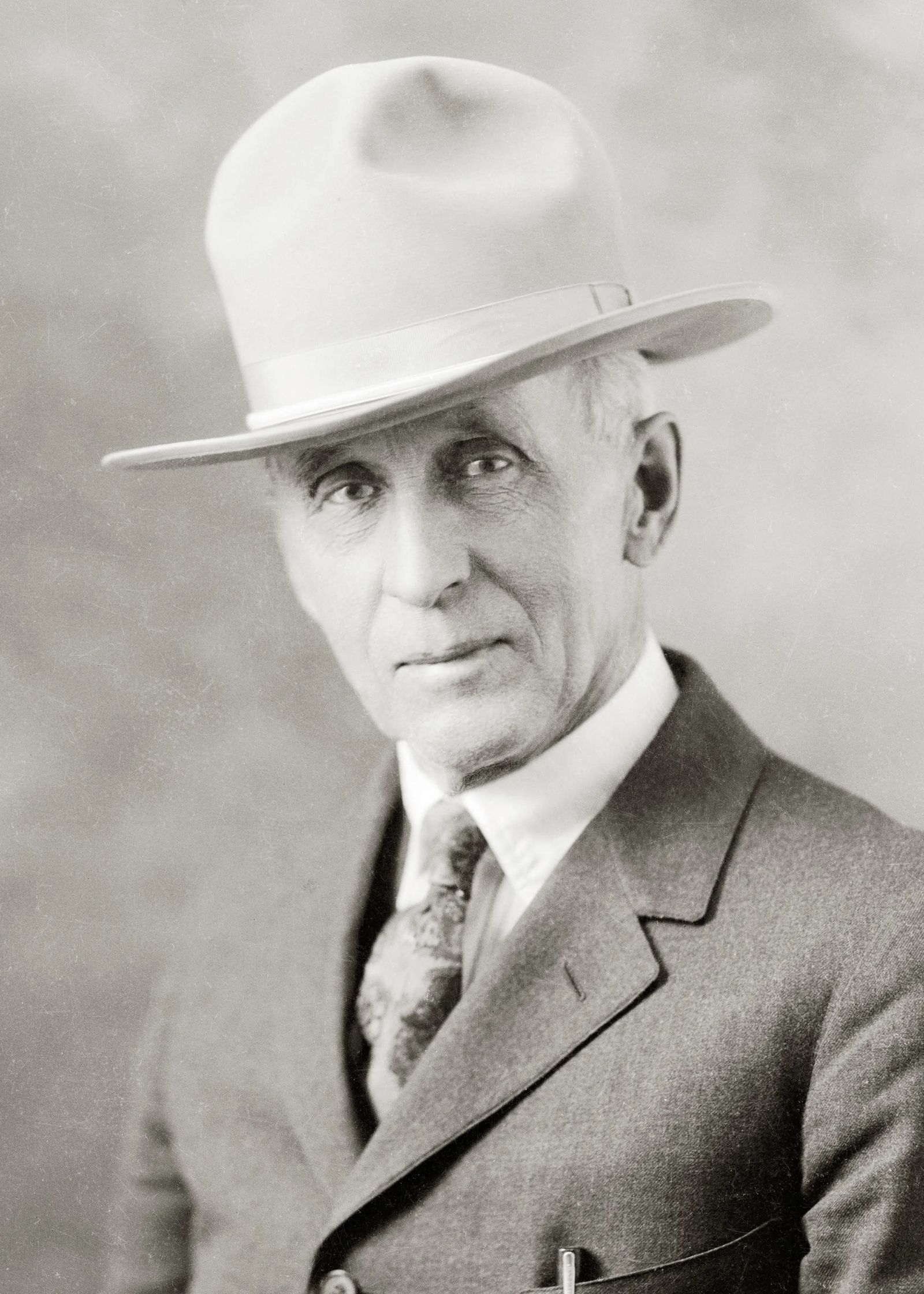

LATON ALTON “L.A.” HUFFMAN (1854 – 1931)

DISTRICT 3 – YEAR 2023

Western historian J. Evetts Haley proclaimed that L.A. Huffman’s photographic work “surpasses all for historic subject matter close to the range.” Laton Alton Huffman was born on October 31, 1854, on a frontier farm in Winneshiek County, Iowa, to Perrin C. and Chastina (Baird) Huffman. L.A. learned photography from his parents, and the business briefly operated as P.C. Huffman & Son. By 1876, L.A. had moved 15 miles south to Postville to open his own studio. Among various endeavors, Huffman worked during 1876 at the studio of F. Jay Haynes at Moorhead, Minnesota.

In December 1879, Miles City’s Yellowstone Journal noted L.A.’s arrival at Fort Keogh, an Army outpost built in response to Custer’s defeat in 1876. Huffman became post photographer, an unpaid position that provided a log building with a dirt floor for use as studio and residence. Prior post photographers, John H. Fouch and S.J. Morrow, had not prospered. Huffman was the first to succeed and remain in Montana.

The 25-year-old Huffman opened a Miles City studio during the summer of 1880 on what would now be the 100 block of South Fifth Street. Hustling to earn a living on the frontier, Huffman began a partnership with Eugene Lamphere during the fall of 1880 to establish a small cattle ranch near present-day Lame Deer. During his early years in Miles City, Huffman participated in winter buffalo hunts. He preserved the only known photographs of buffalo hunters at work on the Northern Plains, skinning hides and removing tongues. After 1883, the large herds were gone.

Huffman worked as a guide and photographer for hunting expeditions, often several weeks in duration. An early client was George O. Shields, editor of The American Field magazine. Its December 1881 issue was the first national publication known to feature Huffman’s images.

Another significant client was William T. Hornaday, Director of the New York Zoological Park. Bones found on their earlier hunting trip and details of a 1902 Huffman letter to Hornaday came to the attention of paleontologist Barnum Brown. Using that data, Brown organized extensive excavations at the Hell Creek Formation near Jordan that yielded the first documented remains of Tyrannosaurus rex.

Theodore Roosevelt visited Huffman’s studio in 1884, and later displayed six large Huffman prints in the White House. Frederic Remington used Huffman photos, likely supplied by Roosevelt, as direct models for some illustrations published with Roosevelt’s accounts of his time ranching in Dakota Territory.

Huffman’s largest volume of work documented cowboy life, often capturing stunning action shots with cowboys, horses, and cattle in motion. Huffman was not a “stand still and face the camera” photographer. Rather, he had the instincts of a photojournalist, and his knowledge of cattle, horses, and area terrain allowed him to anticipate the right position for great captures.

Additionally, Huffman preserved a visual history of sheep ranching. His photos of solitary herders and their wagons, huge flocks of sheep, and busy shearing pens documented an era when Montana was home to as many as six million sheep.

Huffman’s early photos were taken with a two-lens camera that allowed production of stereoscopic viewing cards. In 1885, he assembled a single-lens camera from mail-order components. Research on vintage equipment indicates a probable camera weight of 8 to 14 pounds. With tripod, a supply of 6.5 x 8.5-inch glass-plate negatives, and lenses, Huffman might have carried 50 pounds of gear to distant locations. While most photographers mounted their cameras on tripods for studio portraits of subjects rigidly posed to prevent blur from motion, Huffman was not only capturing action shots in remote locations, he obtained some from atop his horse — testimony to Huffman’s steady hands and a well-trained mount. Huffman’s photo “Bucked Off,” from not later than 1898, was the nation’s first known photograph to capture a bucking horse and a cowboy riding the empty air above. The photo was taken not in a rodeo arena, but on unfenced range. Not until 12 years later was another cowboy photographed in midair, and that was inside a rodeo arena.

Huffman corresponded with people of national stature, in addition to Shields and Hornaday. They included pioneer Granville Stuart, writer Hamlin Garland, poet Badger Clark, frontiersman Yellowstone Kelly, ethnographer Frank Bird Linderman, and historians George Bird Grinnell and O.D. Wheeler. Former Huffman employee Thomas N. Barnard later gained fame for his photos of mining life near Wallace, Idaho.

L.A. Huffman obtained national exposure from appearances of his photos in numerous books and magazines. Awareness of his work was boosted by two series of postcards he sold, and a series of color postcards distributed by the Northern Pacific Railway. To reach a larger market without having to individually produce prints, Huffman outsourced collotypes, produced in quantity by a commercial printer, for more than 50 of his most popular images.

During 1951–55, historian Mark Brown and W.R. Felton, Huffman’s son-in-law, engaged Jack Coffrin at his Miles City studio to produce hundreds of prints from Huffman’s negatives. The prints served as artwork for The Frontier Years (1955) and Before Barbed Wire (1956), books that provided unique details of Montana history.

Huffman’s historically significant images continue to be published, including superb portraits of important Northern Cheyenne and Sioux chiefs taken after surrender at Fort Keogh. His photographs of Spotted Eagle’s village during the winter of 1880–81 were perhaps the last in history showing a camp with tipis made from buffalo hides. Huffman’s captures of a Diamond R bull-train preserved a scene that would not be repeated after the Northern Pacific Railway’s 1881 arrival at Miles City.

L.A. Huffman was elected in 1885 as Custer County Commissioner and in 1893 as Representative to the Montana House. He died in 1931 and was interred at the family plot in Custer County Cemetery. In 1976, he became the first and only career photographer inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.

References

Allen, Gene and Bev Allen. The Collotypes of L.A. Huffman: Montana Frontier Photographer. Helena: Riverbend Publishing, 2014.

Allen, Gene and Bev Allen. The Postcards of L.A. Huffman: Montana Frontier Photographer. Helena: Sweetgrass Books, 2018.

Brown, Mark H. and W.R. Felton. Before Barbed Wire: L.A. Huffman, Photographer on Horseback. New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1956.

Brown, Mark H. and W.R. Felton. The Frontier Years: L.A. Huffman, Photographer of the Plains. New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1955.

Peterson, Larry Len. L.A. Huffman: Photographer of the American West. Tucson: Settlers West Gallery, 2003.

Peterson, Larry Len. L.A. Huffman: Photographer of the American West, second edition. Missoula: Mountain Press Publishing Co., 2005. (Softcover with same content as first edition.)

Peterson, Larry Len. L.A. Huffman: Photographer of the American West, revised third edition. Missoula: Mountain Press Publishing Co., 2013.

Notes

Documentation for the 1898 or earlier date for “Bucked Off,” Huffman’s capture of a cowboy in midair, was furnished by a listing in Huffman’s 1898 catalog, scans of which were provided by collector and scholar Gene Allen of Helena, Montana. To date, the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum and others have cited Ralph R. Doubleday’s 1910 photo as the first in American history to preserve such an image. Huffman’s remarkable capture on the open range was 12 years prior.

To present a credible weight range for Huffman’s camera, research was performed using early mail-order catalogs of photographic gear, past auction listings, and data from online blogs on antique cameras. Earlier accounts had consistently accepted Huffman’s claim of 50 pounds as a camera weight, rather than as an aggregate tally of gear he might have carried. On long excursions, Huffman likely hauled additional supplies by wagon.