-skelton-courtesy-photo-2016.jpg?fit=outside&w=1600&h=2212)

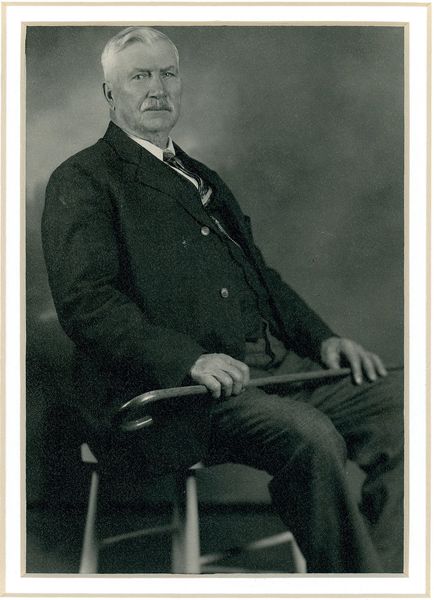

MCHF & WHC HALL OF FAME INDUCTEE 2016

William "Bill" Skelton (1850-1943)

William “Bill” Skelton was born in Cumberland, England in 1850, and came to the United States, settling in New York, with his parents in 1865. His father, Henry was a farmer by trade. His mother, Martha (Chambers) bore eleven children, of whom William was the tenth.

Bill soon thereafter went to Canada, and worked for a farmer for $6 a month. In 1866, he returned to New York, but found his parents had gone back to England. Bill made the decision to travel to Sioux City, Iowa, then on to Fort Benton, Montana earning passage by working on a riverboat. He joined with The Old Fur Company, and helped them build a trading post for Indian trade on the Missouri River at Fourchette Creek, above the mouth of the Musselshell. After the post was built, Bill honed his skills as a hunter and wolfer, and was very successful at both for a number of years. He spent much of his time in the area between Fort Benton and Fort Peck, Montana. The animals were very plentiful in those days. Bill related that he killed deer, elk, antelope and buffalo in the thousands, and one winter took 500 wolves by trapping and poisoning. He said, in hindsight, taking that many animals was excessive, but at the time, it seemed that the number of animals were inexhaustible.

He eventually concentrated his hunting in the Lewistown area, and loaded his hides on the Diamond R bull trains, where he sold them in Carroll, a major fur trading post not far from Cow Island in Montana. It was during this time that William became friends with fellow hunter/trapper Yellowstone Kelly. They were kindred spirits, and hunted and trapped together.

He owned and operated a woodhawking business on Cow Island, selling wood to the riverboats traveling the Missouri. His wood yard was one of the first to sell pine, along with the cottonwood. This was important to the riverboats, because it burned hotter, and gave the boats more power to get up the rapids.

He was attracted to the gold rush in the Black Hills for a short period. On the way back, Eugene Abbott and Bill missed the last riverboat, so they walked up the Missouri, heading for Fort Peck, and came upon Sitting Bull’s camp. This was shortly after the Indians had defeated General Custer and his army and the young warriors were prepared to kill the white men. As told - Sitting Bull and the other chiefs held them back, forming a bodyguard line allowing them to hide in the willows and access the river. Once they were across the river, and made it to the fort, they were safe and forever grateful to Sitting Bull.

Bill had a thriving business at Cow Island until the Nez Perce uprising cautioned travelers. He was escorting riverboat passengers to Fort Benton while his partner, Charles Buck, followed with added passengers. After maneuvering a rough stretch of the river, Charles’ passengers boarded with Bill for the remainder of the trip and Buck turned back to the wood yard. Unknown to them at the time, the Nez Perce were headed to Canada across the Missouri. Buck was never seen again. Prospectors and others a short distance behind Bill’s party were killed, but he was not aware until his party arrived safely in Fort Benton. A fortunate day for Bill.

While at Cow Island, he took on the unenviable task of blowing out the spring ice jams which formed on the Missouri near there, which opened the river for travel.

In 1878, Bill joined the gold rush to the Bearpaw Mountains, and in 1879 joined the rush to Yogo Gulch. He discovered no gold, but instead another kind of treasure—Vaitleain Vann (Van, Venne), who he wed on December 2, 1879. Vaitleain was the daughter of Peter and Mary (Billguard) Vann, who were both born in Canada. The family owned a restaurant in Carroll, Montana from 1876 until 1878, where it is believed the couple met. Family lore says this was an arranged marriage—she was 15, and he 29. Thus began a new journey for William Skelton.

In 1880 they moved to a piece of land, on Wolf Creek, three miles southwest of Stanford, and proved up on it. To stock the place, he picked up range cattle here and there, usually paying $10 apiece for them. The first winter (1880-1881) was an extremely hard winter on cattle, and Bill was able to get a good start by offering to winter his neighbor’s cattle—in exchange for half of the herd. Since he was on the river bottom, he had good protected range for this.

A short time after moving to the Stanford place, he plowed a furrow, in which to run water, with which to irrigate out of Wolf Creek. This was the first irrigation ditch to be plowed in the Judith Basin, and set a precedent for Montana water rights—giving the Skelton’s first water rights to their land. A right upheld in the courts. It is noteworthy that this act was captured in a painting by Charles M. Russell, and captioned “The First Furrow.”

An interesting story is told on how Bill “chinked” his cabin for winter. He thought it too tedious to fill the cracks with mud, and also liked the breeze that came through the logs in summer. When it got cold, and there was snow on the ground, he would shovel the cracks full of snow, and as the snow began to melt, he let the fire go out. When ice filled the gaps—voila! Chinking! However, it is said he had “to adjust the intensity of his fire to the degree of coldness.”

The killing winter of 1886-1887 was legendary in Montana. The only surviving cow at the home place was the milk cow. Other surviving cattle were found as far away as the Judith River, forty miles away. It was devastating, but gradually they built their cattle herd back up. At the peak of the operation (1900-1910), they ran a 1000 sheep, 150 head of cattle, and 500 horses.

Bill was a successful stockman, but his real interest and passion was always hunting, Vaitleain was quoted as saying that “many times Bill Skelton would neglect his ranch chores to take any hunting trip which came along”. They never lacked fresh meat which was good, as they were the parents of 11 children. In old age, Skelton’s sons took him hunting every year - he was a provider until the end.

Bill was an early member of the Montana Pioneer Society, and was honored in 1942 at the Cowboy’s Reunion in Great Falls. He passed away December 20, 1943. Bill and Vaitleain are buried in Great Falls.

Resource: Skelton Family History