-schall-2014-legacy-photo.jpg?fit=outside&w=403&h=580)

Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame INDUCTEE 2014

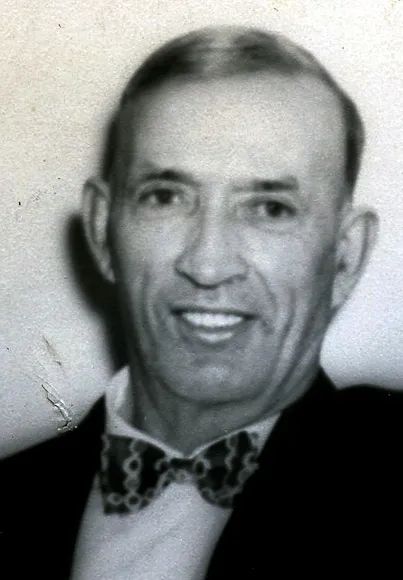

William “Ed” Schall (1883-1970)

“A race horse runs in a hole in the wind” -- Ed Schall

William “Ed” Schall sat loose in the saddle as he rounded up his latest herd of horses. It was sometime between 1907 and the early 1920s in the Jocko River country near Arlee, Montana. Ed, his brother Reuben and Ed Lane partnered as they bought horses from the three Native tribes recently placed on the Flathead Indian Reservation. The Flathead, Coeur d’Alene and Spokane Reservations were opened simultaneously to homesteading on April 1, 1909. The three men won lottery numbers and settled there.

Ed was born in 1883 in Armstrong, Pennsylvania, to William Schall and Eliza Emily (Cook) Schall. This is the time of the enormous bison slaughter on the Great Plains and the opening of trade and commerce in the West, with help from the railroads. When Ed was a young man he was over six feet tall with broad shoulders, strong back and large capable hands. He split oak ties for the local Pennsylvania steel mill for ten cents a tie claiming he could cut ten a day. Ed had skill with an axe and could throw a heavy mall (hammer) long distance. Years later he would build his two-story barn by hand.

Ed's father lost his money with a bad bank loan and couldn’t offer his children much. Ed’s brother was a school teacher and a sheriff in Spokane, Washington. Ed turned his back on his harsh living conditions and took off for Indian country and the business of horse trading. It was estimated that 1,500 Flathead Reservation Indians owned 45,000 Cayuse and Pinto horses. The Plains Salish people of the Flathead were also renowned for their colorful Appaloosa ponies they traded with the Nez Perce in Idaho. Many tribes all over the Northwest had horses for sale.

Ed traveled as far south as Utah, where it is rumored he bought a horse from Butch Cassidy. Lore has it that they swam a herd of horses across the Columbia River in the days when it was a free-flowing river. Once the horses were rounded up, Ed and his partners worked with a local tribal member named Michel Kaiser to break the horses to a saddle. Kaiser’s fast roping style brought the horses down with a quick loop around their front legs. After the horses became manageable, they were loaded onto boxcars from the siding in Arlee of the Northern Pacific spur line that ran out of Missoula to Arlee.

Ed and partners rode with their horses back East to downtown Pittsburgh where they set up a rope corral on the street and sold them to stylish Atlantic seaboard families. The partners had a government entrepreneurial license, the rope corral was an ingenious way to avoid a stockyard, and they had relatives in the area with whom they could board. An Indian horse went for $5.00 apiece and the final sale was usually $20.00 per horse. The hard work and adventures of horse trading beat living in his father’s empty house and cutting ties all day.

Ed liked the Jocko River country for its mild weather, referring to it as the banana belt. It sported good pasture land before the irrigations project (circa 1916) which introduced farming into the area. For the rest of his cowboy career, Ed raised beef, bought beef from the Indians and ran a slaughterhouse. He sold meat to the logging camp in Valley Creek and sold to various butcher shops. He married twice and raised eight children. Ed did what needed to be done to live well and raise his family, but his passion was horses.

In 1920 the US Army devised a clever scheme to “seed” Thoroughbred studs throughout farms. This plan, The Army Remount Program, was designed to improve horse quality in the country and replace the horses and mules lost overseas in WWI. It operated on the premise that philanthropic Thoroughbred breeders would donate studs to the Army, or the Army would buy the studs outright. Each stud was placed in service for three years with civilian agents. “These agents were horsemen and displayed community vision and generosity.” Ed qualified and received his first stud, Hiram. The Army purchased three-year-olds “in good condition” for $150.00. The agent paid for all the costs of the horse after he was delivered but could charge a stud fee. This was normally $10.00 minimum or as high as $20.00. The young horses had to be a certain size and color to qualify for the uniformity standards of the Army mounted Cavalry. The last shipment of horses from the Schall place was in 1943. Ed’s wife Ann thought the foals would be crushed in the boxcars so she kept them and raised them on bucket feed. The Remount program ended in WWII during the Burma Campaign.

Ed Schall was a man of habit. He wore bib overalls and plain shirts. He did all his chores in simple black lace up shoes or Indian moccasins. If the weather was wet he donned a pair of rubber galoshes. Each afternoon he took a reading break. He sat in a rocking chair and read circulars and always the Thoroughbred Record, memorizing blood lines. During the Remount years, those Thoroughbreds were not to be used for racing, but race tracks were common around the Jocko Valley, including Ed’s place. He and his neighbor, Isaac Plant, owned outright a Remount mare. She cost $300 from the Army. Ed was the handler and Isaac was the exercise jockey. Her name was Gramanet, and she dropped several good racers. Ed developed a life-long love of the sport and retained a continued habit of reading the Thoroughbred Record.

One day during WWII, he saw an ad in the Record for the horses belonging to a Whitney of the Llangollen Stables. The man was missing in action, and his horses were for sale. Ed bought a high class stud named Flying Scot. He was chestnut with a small white blaze and one white sock. As a three-year-old, he won the Withers at Belmont Park, Long Island as well as the Arlington Classic. That same year he came in third in the Preakness against War Admiral. Breeders came from all over with their mares. Flying Scot stood at stud for many years. He was retired in the 1950s, living into his late twenties.

Ed maintained a large band of brood mares until late in life. He continued racing into the 1960s. His horses did well at local fairs and race tracks around the Northwest. Ed’s last stud was Birmooda. He was full of heart and speed, but he was small in a racing world that was breeding larger, sturdier animals. Ed’s way of life was coming to a close.

Ed lived until 1970 and died at the age of 87. Even into his last years his family remembered him with a slight limp (from an old dancing injury) when walking from his house to the barn where he usually had a foal or a growing horse that needed handling. He got a bridle and a lead rope on them early in their training. He stood as the horse ran in circles or sat on a stump, leading the horse back and forth, telling stories to visitors. He believed in the power of copper bracelets to heal arthritis in horses as well as people. Ed had seen his farming days evolve from plowing with a Percheron team to using a tractor. He lived in the time of traveling by horse to seeing a man walk on the moon. He was old-fashioned in a modern world, with a love of beautiful horses that was timeless.

Selected Bibliography:

Ambrose, Stephen E. Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996.

Fahey, John. The Flathead Indians. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1974.

Lutz, June Shaull. A Historical Account of the Schall/Shaull Family. Grand Rapids, MI, 1968.

The New York Public Library Desk Reference, 2nd Edition. General Information dates. New York, NY: Macmillan General Reference, 1997.

Ronan, Peters. Historical Sketch of Flathead Indian Nation. Minneapolis, MN: Ross and Haines, Inc., 1890.