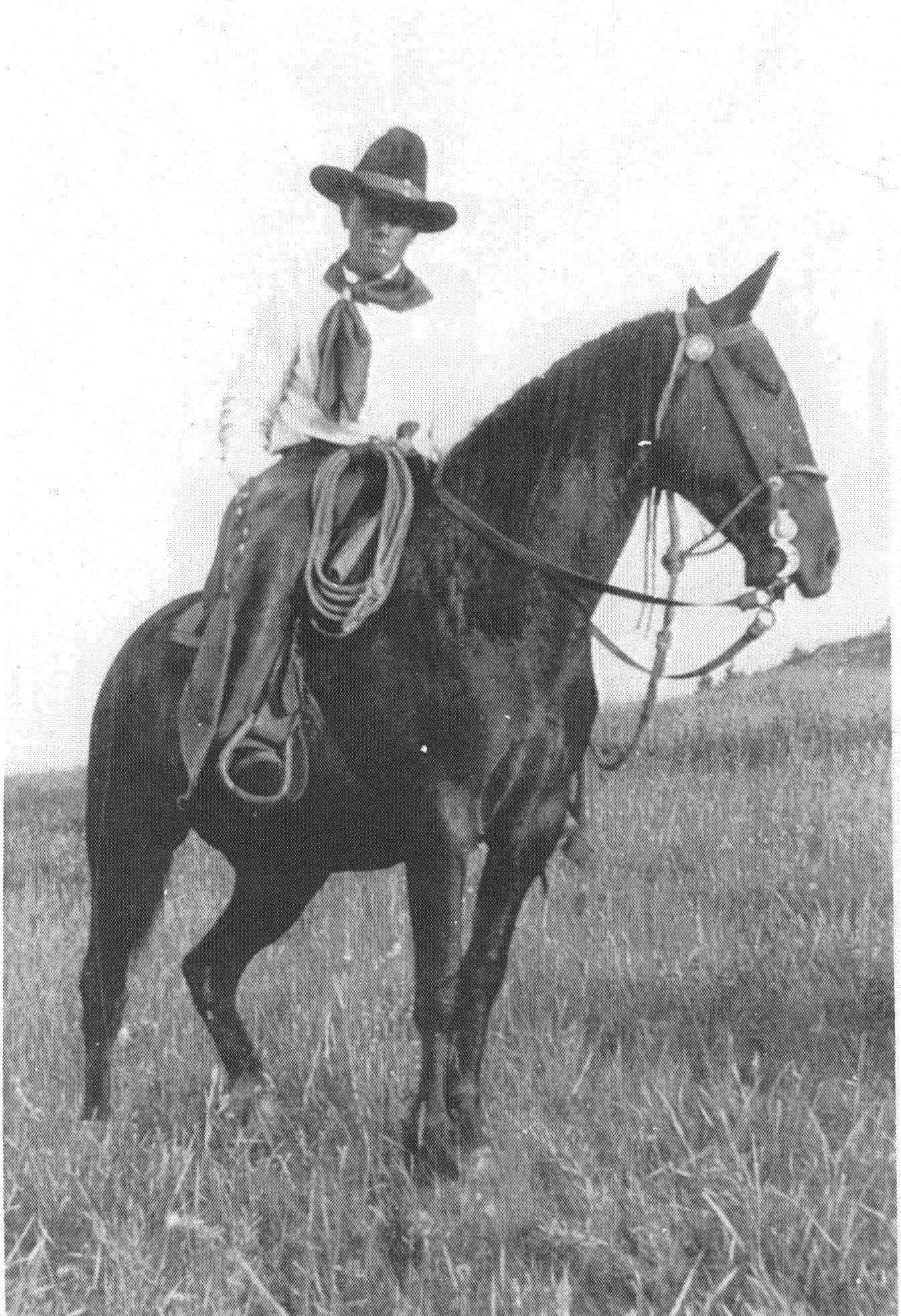

2011 MONTANA COWBOY HALL OF FAME LEGACY INDUCTEE

1860 – 1960 LEGACY AWARD DISTRICT 9

Johnny Flowers (1892-1963)

Johnny Flowers was a true Montana cowboy all his life. For years he was the foreman of the Flying D Ranch southwest of Bozeman. Jim Overstreet and I grew up among people who believed that men who rode and roped and handled cattle were an elite class. Johnny was elite all right but only a little more so. To the generation of cowboys in southwest Montana thirty years older than me—the cowboys I admired and wanted to emulate—Johnny was larger than life. When they talked about him you could hear reverence in their voices. I can still see them in their boots and Levi’s lounging in our barn on a Saturday afternoon. Their conversations revolved around cowboy things that they’d seen, or done, or tried to do. Sooner or later, someone would say, “Well, Flowers said …” or “One time I saw Flowers ….” In their world he was the best. While they didn’t always try to copy him, whatever he’d done was always regarded as the right way.

Johnny was born in 1892 on a small ranch south of Big Timber, on the East Boulder River. His father was a second-generation Norwegian American who rode from California to Montana. His Indian mother was a half blood, and her parents had moved to the Boulder River country from Oregon. Johnny was tall and had a sandy complexion. He took after his father’s side of the family. Proud of his heritage, he sometimes referred to himself as a red-headed Indian.

Johnny started working on the Flying D in 1912 or ’13. Years later, Lyman Wilcox described Johnny’s first day on the job in less than glowing terms to Sam Spring. Apparently, the horse Johnny rode that day was pretty much a bronc. “Johnny came in without his hat that night,” Lyman said. “Nobody figured he’d last long.” From that inauspicious beginning when he was afraid to dismount to retrieve his hat, Johnny lasted until he couldn’t ride anymore, nearly fifty years later.

Although he was married twice, Johnny lived most of his life out of the bunkhouse at the Cow Camp where he used the tanned hide of a bay horse as his bed spread. Witnesses claim that each morning his hat went on his head before his pants. He wore old-style boots with two-inch underslung heels. When he grew older, he could barely walk without them. Johnny cured rawhide and braided bosals and rawhide ropes. The old-time cowboys who worked with him regarded him as an artist with a rope. He used rawhide reatas only on special occasions and usually preferred the hemp rope that was standard until after World War II. When other cowboys began to use nylon lariats, he stayed with the hemp. Even after he got old, he would use an old raggy rope and drag as many calves to the fire as anyone.

Some of what made Johnny special was the way he treated people. It couldn’t have been easy for the boss to live in the bunkhouse with his subordinates and be their friend as well. Johnny seemed to do it without difficulty. Curiously, he never told the crew what they were going to do on any given day. They’d follow him until they got wherever they were going, and then he’d send them this way or that. He never yelled at anyone. When they were working and someone got in the way, or did something wrong, he’d wait until they were alone. Then he’d tell the cowboy a story or make a suggestion without insulting.

Johnny did get demanding when it came time to work cattle. He didn’t want anyone yelling or even slapping their leg. He wanted both his horse and the cow to be able to concentrate on what they were doing. He could read a cow’s mind and worked her easy with small movements at the right time. Instead of insulting the cow, he’d give her that split second, she needed to figure out where she was supposed to go. Whether it was one cow or several thousand, Johnny made handling cattle seem effortless. He worked cattle unhurriedly but efficiently. He managed it all with a minimum of words. The other cowboys learned to watch him and read his mannerisms. They might be driving cattle into a bunch to cut out strays, and Johnny would look back at one of the other cowboys. With the slightest nod, he’d tell him to wait there. Or he might cut a critter from the herd and merely glance at a certain gate that he wanted opened. Sooner or later, everyone I talked to who cowboyed with him would say, “He’d look at you and you’d know you were in the wrong place” or “that he wanted you to….” “A mean look?” I asked Sam. “No,” he replied. “Just a look.”

The words of Roy Laird might have come from any of the cowboys that I interviewed, but Roy said, “It was a privilege to work with a man who knew so much and taught us so much.” Charlie Nelson, the cowboy who rode “The Bronc to Breakfast” in the famous C.M. Russell painting, dedicated a poem to Johnny. It included the following lines: “When Johnny was a kid, I taught him to punch cows that’s true; Now he has forgot more than I ever knew.”

I barely knew the real Johnny Flowers. I was twelve when he came to visit at our house several times in the months before he died in 1963. He was over seventy then, tall, gray haired, and “stove up.” He wore the scars of his life with dignity, and even then, had an indefinable “presence.” To this day, the Johnny Flowers that my Dad and his friends loved still lives in my mind—he’s wearing a big black hat and ten feet tall.