2010 MONTANA COWBOY HALL OF FAME INDUCTEE

1860 – 1940 LEGACY AWARD DISTRICT 5

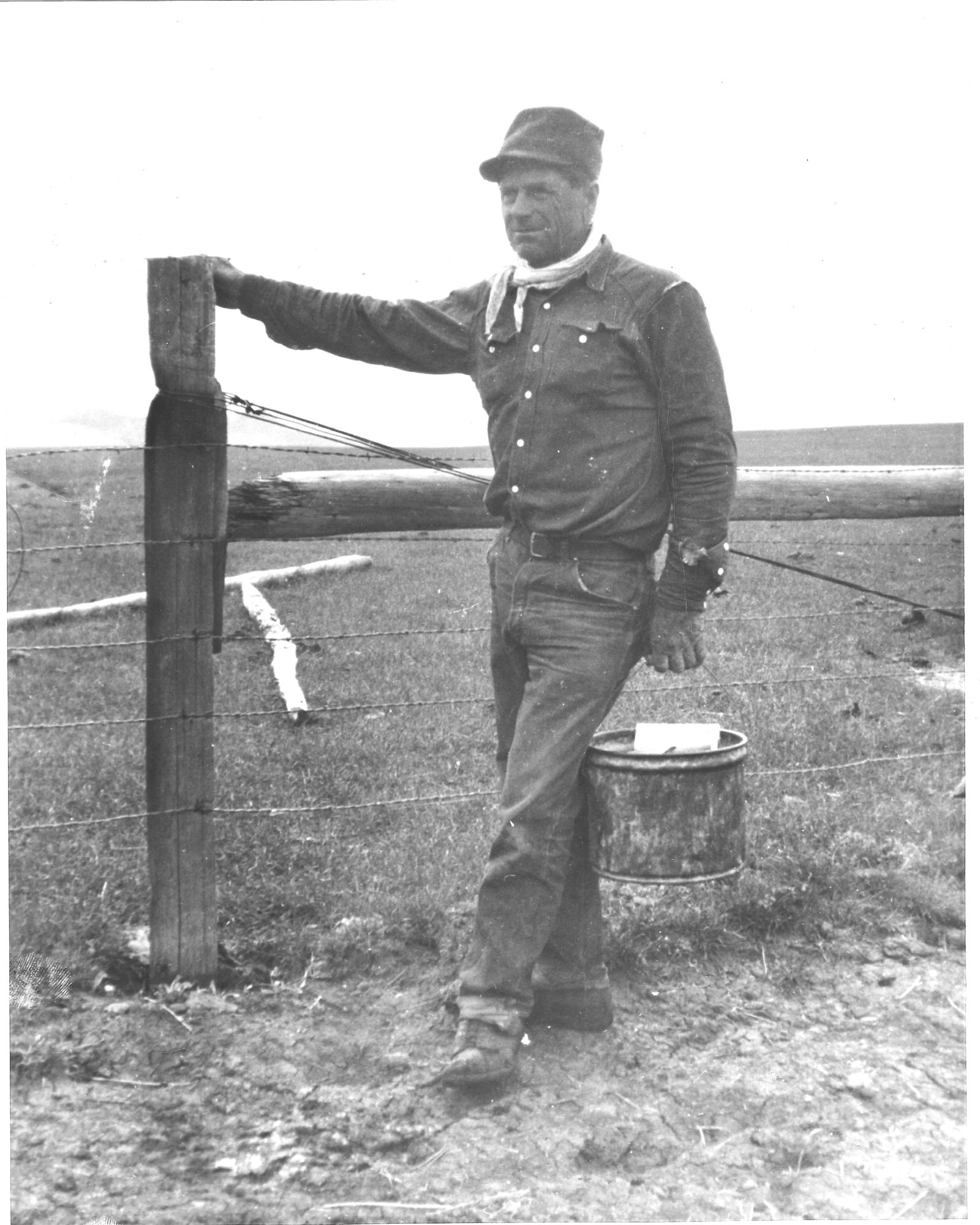

Alvin Frederick Sauke (1894-1995)

Alvin Fredrick Sauke was born September 28, 1894, in Manhattan, Illinois, the oldest of six children. His father, Fred Sauke, read about the Fort Shaw Irrigation Project started in the Sun River Valley by the U.S. government and moved the family to Simms, Montana in August 1908. Alvin was fourteen years old.

The family took a passenger train to Great Falls while the livestock and machinery were loaded and transported on an immigrant train. One of the most distinct and alarming memories Alvin had of Great Falls was the large sign he saw when he got off the train, warning the Chinese, “Chinamen: Don't let the sun go down on you here!” The family lived in Sun River for four months until their home was built in Simms. Alvin enjoyed watching the teamsters unhook the large freight teams and listening to old-timers’ stories tell about the early days in Montana. Alvin had a particularly good memory and could relate these stories to historians of the area many years later.

Alvin was hired on as a horse wrangler that first fall in Montana on one of the last of the big open-range roundups. This covered the vast territory from the Rocky Mountains International Boundary Line, north to the Bow River and south between the Teton and the Missouri rivers of Montana.

When he was sixteen and seventeen, he worked for two local ranchers in the Simms area to financially help out the Sauke family. The ranchers were excellent horsemen and taught Alvin the finer skills of handling horses. He also hired out to help dig the canal and irrigation ditches.

In 1911, before he owned any land or cattle, he bought and registered his own brand E Bar Lazy 2 which is now registered with his granddaughter.

On August 17, 1915, Alvin was combining wheat when a violent thunderstorm began. He put the four-horse team in the barn and ran for the house, getting drenched on the way. His mother gave him a chair on which to sit by the door. A bolt of lightning struck the house, came down the chimney to the kitchen stove, bolted to the floor, and followed the nails on the floor to where he was seated and shot up his wet legs and spine. He was knocked out, the house was on fire and because the burst had melted the nails in the windows and doors, his mother could not open them so she promptly dragged him outside. After the fire was out, Alvin was carried into his parents’ bedroom. That night he subconsciously destroyed the mattress fighting the pain. His parents were unable to take him to the hospital that evening, which was 35 miles away, until the next day as the roads had turned to gumbo following the rain. The doctors didn’t think Alvin would live and if by chance that he did, they predicted Alvin would never walk again. The boy was unconscious for seven days. After two months in the hospital, he was released and taken home on a stretcher. Determined not to be an invalid, Alvin first learned to crawl. He was in a wheelchair for a time, but in a few short months was able to hobble around on crutches. His legs never did regain much strength, but he taught himself to walk by throwing or swinging his arms and dragging his legs. If he stopped walking, he had to be prepared to sit down immediately or lean against something. Admirably for the next 75 years Alvin Frederick Sauke walked on his own by pure determination.

During the timeframe he was a single man, he drove large freight wagons pulled by eight to ten horses for T.C. Powers.

In 1917, Alvin filed on a homestead and gradually managed to add 24 more parcels of land to his property. In 1919, he married Florence Johnson. They were partners in life for 56 years, with Florence working right alongside Alvin until her death in 1976. They had five children: Norma, Robert, Roxana, Bonnie, and Ida.

Tragedy appeared in Alvin’s life when in 1937 his daughter, Bonnie, was killed when struck by an oil truck with no brakes after she got off the school bus. As difficult as it was time traveled on.

Alvin was a horseman all his life. He never really liked cars and threatened many times to drive them over a cliff when he couldn’t get them started.

One cold day in the winter of 1944, the temperature was close to 35 degrees below zero. Alvin had some cattle in a pasture six miles from home. He rode out to feed hay and break the ice in the water trough. While he was busy with the chores, his horse got into some moldy hay that had been discarded. Alvin started for home and rode about a mile when the horse reared, threw Alvin, then stepped on one of his legs and broke it. He knew he had to keep moving or he would freeze. Alvin had to crawl and lead the colicky horse about four miles before the horse began to walk steadier. Alvin then pulled himself onto the horse and rode the final mile home. Florence had stayed up waiting for him noting it was 3 a.m. before she heard his long awaited yell.

On one occasion Alvin made arrangements with a cattle buyer to sell his calves at a named price. The next morning, it was reported on the radio that the price of cattle had spiked. Regardless, Alvin, true to his word, had sold his cattle to the buyer who arrived first thing that morning with a contract in hand for signature at the price they had previously agreed to. Alvin was often respected because of his honest dealings.

His wife Florence died when Alvin was 80 years of age. He lived alone in his home at Simms and cared for himself; cooking, chopping wood for his cook stove, mending fences and driving to town for his groceries and mail until he was 95. After his 95th birthday, he moved into the Skyline Lodge in Choteau. He died in 1995 at the age of 100. He is buried next to Florence at the Sun River Cemetery.

Alvin never gave up on living and never asked for assistance from anyone outside his family. His life is a memorial to the times when hard work, sincerity, and a good sense of humor helped a man succeed in life. This is Alvin’s greatest legacy left to his family and future generations.