2009 MONTANA COWBOY HALL OF FAME INDUCTEE

1860 – 1920 LEGACY AWARD DISTRICT 4

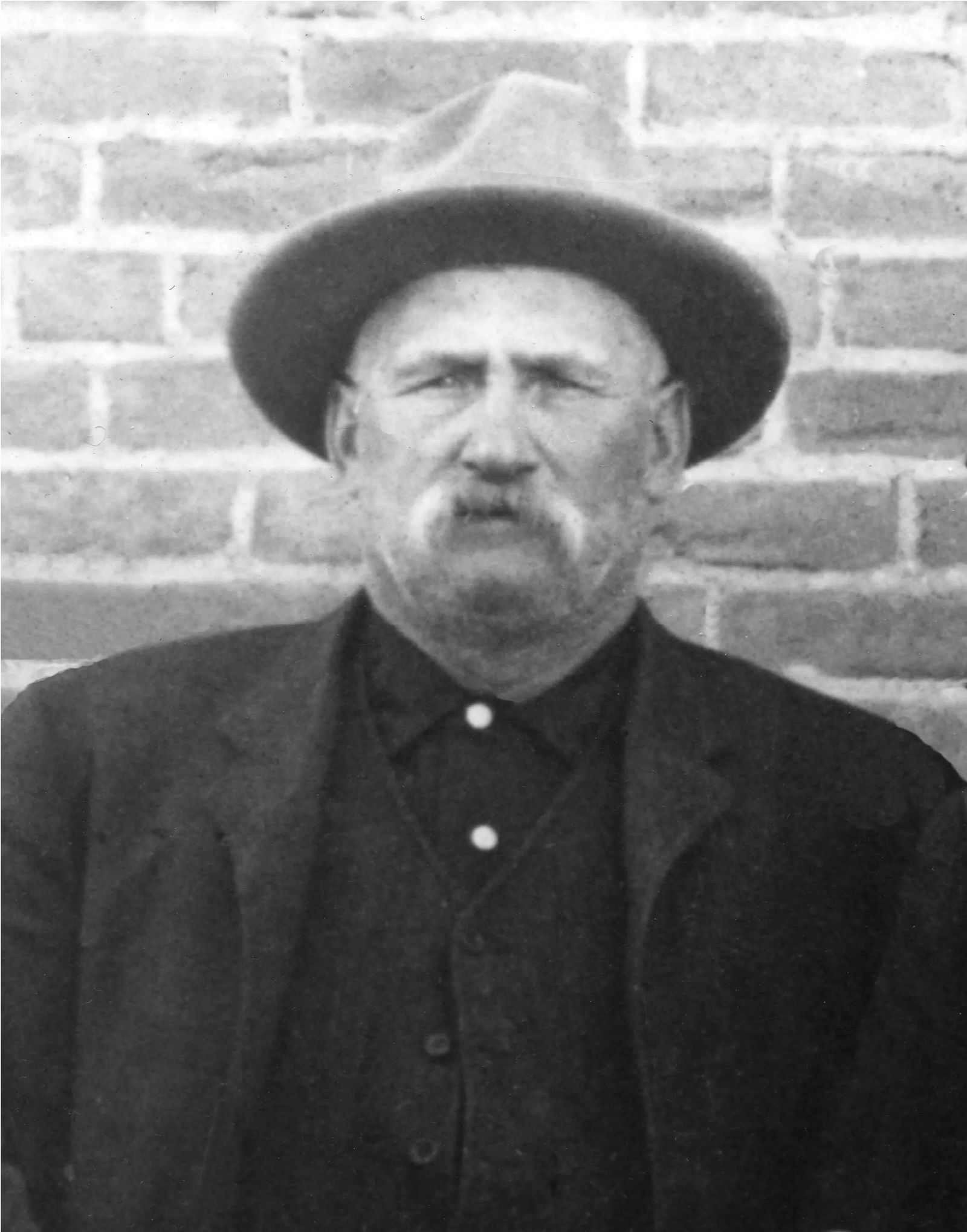

Louis Shambo (1846 – 1918)

Louis Shambo of French descent was born in Louisiana in July 1846. His parents moved to Minnesota when he was six. His formal education was very limited, having attended a Roman Catholic school only briefly. His given name was Louis Chambeau. The Chippewa called him “Louie,” and a misspelling on his first paycheck from the U.S. Government changed his name to Shambo. From that day forward he went by Louie Shambo. He is reported to have good naturedly remarked, “That way if I get in trouble it won’t reflect on my folks.”

Settlers in Minnesota were few and far between in the 1850s, and Louie’s friends were his Chippewa neighbors. Astride a grey horse his father gave him to ride to school, twelve-year-old Louie and an Indian friend ran away from home. The two young adventurers pulled out for points west.

In North Dakota, Louie and his friend lived with the Sioux and Assiniboine Tribes in the Turtle Mountain area. He stayed there a few years, learning their languages and culture, and traveling with them into eastern Montana on buffalo hunts.

He also spent time with the Crow, Cheyenne, and Shoshone people of southern Montana and Wyoming. Learning the Indian ways would later serve him well as a scout for the U.S. Army. In all, he could fluently speak six Indian languages as well as French and English, and was also proficient at Indian sign language.

He traveled around the West, from Colorado to Nevada to California and ventured back to Nevada where he worked as a cowboy for the Nevada Ranch outfit. Louie trailed multiple herds of cattle for the ranch.

In northern Montana, Louie went to work as a packer and scout for General Phil Sheridan. His jobs were many and varied, but one of the most interesting was riding south to Denver to get the military payroll and carry it in a money belt back to Fort Assiniboine. Because of his trustworthy nature, he was also called upon to make trips north to the forts in Canada. He refused to discuss the nature of the business or dispatches that he carried, but only remarked, “They were secret.”

Louie worked with Yellowstone Kelly as a scout for General Crook. When concern with the Nez Perce began to brew, General Nelson A. Miles attempted to hire Louie as head scout. He’d be paid top wages, offering him $75.00 per month. Louie wasn’t impressed with General Miles’ arrogant, assuming manner. Besides, he was making $125 per month as a packer at Fort Assiniboine. He did tell the General that he might consider scouting for him for the same wages, but the General refused. Being the independent Westerner he was, Louie told General Miles he’d see him in hell before he’d work for him for $75.00 a month.

That would have normally ended any meaningful negotiations, but as the Nez Perce headed east out of their Idaho homeland, raiding and burning the bull trains destined to supply the frontier forts. General Miles again sent for Louie Shambo, this time saying that money was no object. He would pay Louie $300.00 per month and give him ten Cheyenne scouts. Louie agreed.

In the end, six Cheyennes were hired to help scout. In short order they cut the trail of the Nez Perce band north of the Bears Paw Mountains. When they saw the Nez Perce horse herd, Louie sent a scout back to General Miles with the news, while he and the remaining Cheyennes waited for General Miles' arrival.

The Nez Perce were camped at Snake Creek, approximately 17 miles south of where Chinook, Montana, is now located, and a mere 40 miles from the Canadian border where safety awaited. General Miles with the 2nd and 7th cavalry and the mounted 5th infantry, led by Shambo and Cheyenne scouts, followed the tribe’s trail, but didn’t catch sight of them until a mere 80 yards away. General Miles ordered the bugler to sound double quick, and the 7th Cavalry charged the Nez Perce camp just before noon on September 30, 1877.

The Nez Perce were well fortified and lying in wait for the attack. The charge was repelled, and Louie’s horse was shot from beneath him. He soon expended all of his ammunition as well as that of one of his fallen comrades. Yellowstone Kelly daringly brought him a horse at dusk and the two safely reached the army camp. Louie had killed nine Nez Perce, but throughout the remainder of his life, was not proud of the fact. “It was in the line of duty,” he said.

They buried 22 soldiers from the first day of battle. A lengthy siege ensued, with Chief Joseph finally agreeing to surrender because of the suffering the women and children were enduring due to the cold, and lack of food and shelter. Louie was not pleased when General Sheridan refused to honor Joseph’s terms of surrender accepted by Crook and maintained throughout his life that Chief Joseph was betrayed.

After his service in the Battle of the Bears Paw, the last major Indian battle fought in the West, Louie returned to Fort Assiniboine to work under General Pershing, and later returned to cowboying after the fort was closed. In 1890 he moved to Bull Hook Bottoms, the site of present day Havre, where he worked as a bartender in the winters and hired out to cowboy in the summer.

Louie married a Gros Ventre woman, who bore him five children. His wife later missed her people and moved their children to the Fort Belknap Reservation to be near her family. Louie visited them often, but remained living in Havre.

He was once offered $1500.00 for the rights to his life story but refused, saying, “I’ve still got relatives living, and I’m not money hungry.”

In 1916 when part of the former Fort Assiniboine military reservation opened for homesteading, Louie filed for a claim eighteen miles south of Havre and built a shack in which to live.

Louie Shambo died on November 4, 1918. He not only lived the history of Montana; he was a living part of it. For years both a school and a post office south of Havre bore his name, while the little stream on his old homestead carries the name of Shambo Creek to this day.

Footnotes:

Grit, Guts, and Gusto, 1976 Hill County Bicentennial Commission The Life Story of Louis (Chambeau) Shambo, by Mrs. Vina Stirling. The Havre Daily News, July 29, 1960.

The Chinook Opinion, August 23, 1956. The Blaine County Museum, Chinook. The H. Earl Clack Museum, Havre. Louis Shambow, by A. J. Noyes. Land of Chinook, by A. J. Noyes. Montana Historical Society Archives www.friendsnezpercebattlefields.